Overview

In this project, I tackled simulating celestial bodies moving based off initial positions and velocities. It was fun to play around with initial conditions and masses of the bodies and watch the resulting orbits (or lack thereof). I used C to do the math and Python to display the resulting simulation.

The final result is a Python program that feeds a C program the initial conditions of the system to simulate, and the option to live display the simulation, or simply run the math and then watch it after.

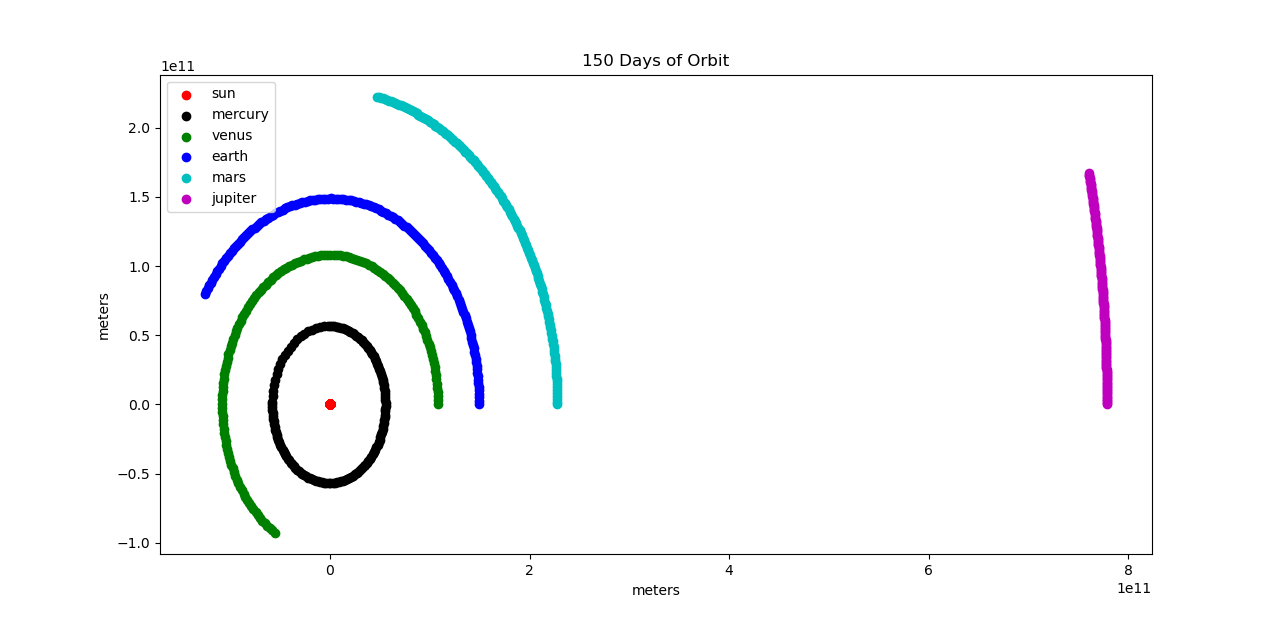

Below you can see what the simulation looked like for a Sun, Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter system that I simulated for 150 days of orbit.

Simulation Process

The simulation works by defining celestial bodies with masses and initial positions and velocities, and then calculating the force they exert on each other over a certain time period (I set that to 300 days). I did this by making a linked list of the bodies, and then recursively going through it to find the interactions between all the bodies. Every second the new force interactions are calculated and manually integrated to find the positions.

Initially, I tried running the simulation in Python, using numpy to do the math, but the Python loops were making the simulation far too slow. I then switched over to C, reasoning I could use C to do the math and then transfer the positions to a python program. I used the same algorithm as I did in Python - making structs for bodies, forming them into a linked list, and then recursively finding their interactions. I then used a serial port emulated called Com0Com to send the data over from C to Python. This worked pretty well, and I could now see the data in real time. I only have the data send through every hour of simulation time (which less than a second in run time for the 6 bodies I made), and then plot it with matplotlib.

A nice change I made once I had the simulation working, was to make it more configurable in runtime. Rather than hardcoding the bodies into the C executable, I let the C program make the bodies in runtime based off of command line arguments that the python program would feed it. This works nicely, as one doesn't have to recompile the C program every time one wants to change the bodies' characteristics. It functions more like a blackbox now.

Below you can see five of the bodies orbiting to scale (the window size is 1600*10^9 meters by 1600*10^9 meters).